Understanding the Illness-Wellness Continuum

Here is a basic framework for health, well-being, and illness.

This essay was authored by Professor Gregg Henriques and was originally posted in UTOK’s Psychology Today blog here.

Ask virtually any mother what they want for their kids, and they will say, “I just want them to be happy!” Although they might have some difficulty specifying what they mean in greater detail, they are not referring simply to the emotion of happiness. Consider that they probably would not be thrilled if their kid was a happy serial killer. What moms really want is for their kids to be high in well-being.

But what, exactly, is well-being? Recently, there have been several journal issues in various academic fields devoted to understanding well-being. This blog gives the answer provided by UTOK, the Unified Theory of Knowledge. We can start by noting that UTOK considers well-being a central concept and value, as evidenced by UTOK’s ultimate justification: Be that which enhances dignity and well-being with integrity. I presume most mothers would want their children to live their lives in accordance with this mantra.

If you look it up in the dictionary, well-being refers to being happy, healthy, and/or prosperous. This definition is helpful in that it extends the concept beyond just feeling positive. However, the deeper meaning of well-being remains unclear.

This becomes apparent when we go to the academic literature. In opening their special journal issue devoted to positive psychology and well-being, Resnik and Mercer (2024) state that “well-being is a difficult construct to grasp and define due to its complexity and the individual variation in how it is experienced” and go on to list various controversies and different ways of conceptualizing it. Similarly, Jarden and Roache (2023) open their special issue on well-being by saying that “a clear and useful definition and conceptualization of well-being remains elusive, a situation which has manifested historically, contemporarily, to the public, and within and across disciplines.”

UTOK claims that it does not have to be this way and provides us with the “Nested Model” to define the concept with richness and depth in a way that accords with what mothers want for their children.

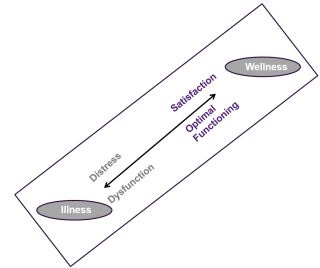

The Nested Model (Henriques et al., 2014) starts by framing the wellness-illness continuum on what we can call the “core dimension.” The core dimension has two aspects, which are feelings and functioning. Feelings refer to the subjective evaluation of how things are going. Functioning is more objective and refers to how well the “system” is operating in its context toward preferred goal states.

Using the core dimension as a lens, we can say that high well-being is associated with feeling good and functioning effectively, whereas low well-being is associated with feeling and functioning poorly. As this blog notes, the core dimension is nicely captured by Walgreens’ slogan, “At the corner of happy and healthy.”

The second piece of the well-being puzzle is to realize that the core dimension is made up of four different nested domains. This is why UTOK labels it the Nested Model. The first domain is the subject domain. This is how the world looks and feels from the vantage point of the individual.

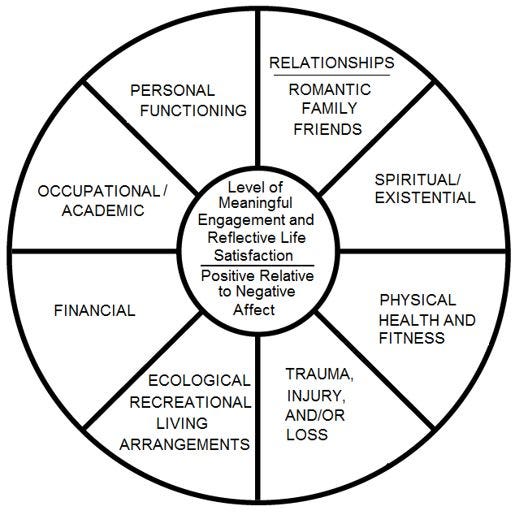

Research has shown that we can divide subjective well-being into four different parts. Two of these domains reside in the primate, feeling portion of our minds (i.e., our core, experiential self), and two reside in the more self-conscious, personal reflective portion (i.e., our egos). The two feeling dimensions are, not surprisingly, the positive and negative feeling states. Basically, how good you are feeling and how bad you are feeling are evaluated on different dimensions because these are different systems.

The two reflective dimensions involve personal evaluations of satisfaction. One is a “general” domain, whereby the individual abstracts across their life and gives a global indicator of life satisfaction. The other refers to domain-specific aspects of their lives. Here is the map of the subjective dimension of well-being, which is given by UTOK.

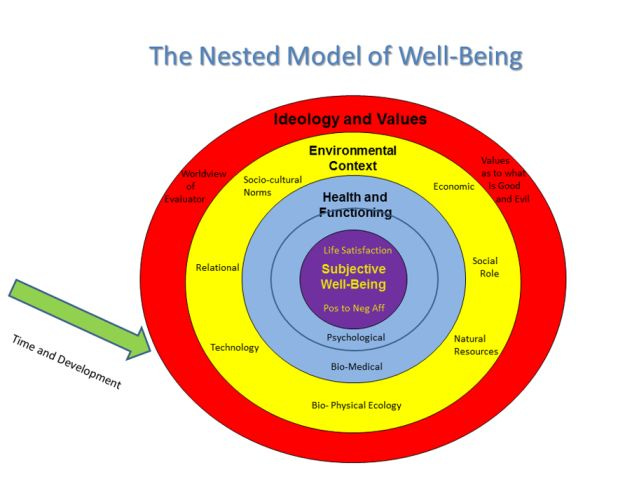

The second domain of the Nested Model refers to the biological and psychological functioning of the individual. Basically, this is how health is assessed by a medical doctor and a psychological doctor. A medical doctor is concerned with things like physiology, anatomy, and diseases. A psychological doctor is concerned with problems in thinking, feeling, relating, or acting.

The third domain of the Nested Model refers to the environmental context. This domain can also be divided into two areas. One is the physical environment, and the other is the social environment.

The fourth domain is the one that is most often overlooked. This is the domain of values. Specifically, it is the domain of the values of the evaluator. The fact that well-being and illness are value-laden constructs can make them confusing for people. However, UTOK helps us see them clearly because it is a sophisticated philosophically-informed model. Here is the Nested Model of Well-Being (and Illness) as depicted in UTOK: The Unified Theory of Knowledge.

The final aspect of the model puts the illness-wellness continuum in the context of time and development. This helps us consider dispositional tendencies like vulnerability and fragility when thinking about illness and robustness and resilience when thinking about wellness. Vulnerability refers to the likelihood of having problems over time, and fragility refers to how sensitive someone is to particular kinds of insults and injuries. In contrast, robustness refers to how strong or impervious someone is to injuries, and resilience refers to how quickly someone bounces back from injury.

So, when mothers say they want their kids to be happy, what do they really mean? If we view it through the lens of UTOK’s Nested Model, they want their kids to feel good and be satisfied with their lives, be biologically and psychologically healthy, and live in rich, safe, and supportive physical and social environments in accordance with wise values, such that they are robust and resilient if and when bad things happen.

References

Henriques, G. R., Kleinman, K., & Asselin, C. (2014). The Nested Model of well-being: A unified approach. Review of General Psychology, 18, 7-18, doi10.1037/a0036288.

Jarden, A., & Roache, A. (2023). What Is Wellbeing? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 5006. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065006

Pia Resnik, Sarah Mercer, Introduction to the special issue on positive psychology and wellbeing, ELT Journal, Volume 78, Issue 2, April 2024, Pages 109–116, https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccad064